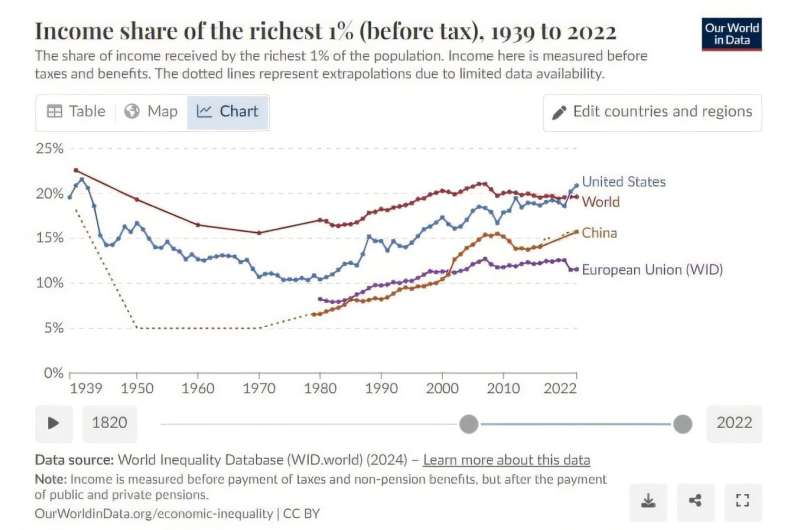

How will artificial intelligence affect the distribution of income and wealth this century? After falling through much of the 20th century, income inequality, measured as the fraction of income going to the richest 1% of residents, has been rising since the 1980s. The fraction has doubled in both China and the United States during that time, increased by 50% in Europe and one-third worldwide.

Industrialization dominated the economy before then, but starting in the ’70s and ’80s, capital took over as globalization increased, tax changes reduced progressivity and game-changing technologies were introduced rapidly.

The computer and personal computer revolution came first, followed by the Internet and the World Wide Web. Now artificial intelligence (AI) is beginning to make its mark in the world as a next-generation general-purpose technology.

Where might AI lead, and how will it change the distribution of incomes? In an article published in the journal Heliyon, two Chinese researchers conclude that while increasing AI automation in economic production will exacerbate wealth inequality, the situation is more nuanced and other factors will help to mitigate these disparities, such as capital-enhancing technologies and “Hicks-neutral” technological progress.

From their numerical analysis, the authors conclude that encouraging AI technological progress will generally contribute to a growth in economic output and improve societal welfare. “AI is poised to become a new catalyst for economic expansion in China, injecting vitality into the economy,” they write.

“Further numerical analysis shows that policies fostering AI technological progress generally contribute to output growth and improve welfare.”

Although this subject has been studied many times before, the new study by Fang Liu of the Economic School of Changzhou University in China and Chen Liang of the Financial Technology School of Shenzhen University included several new contributions to address gaps in previous research.

The team extended the analysis of AI’s impact by including property income and wealth inequality itself—wealthier people have more income options than do the non-wealthy. They used data from China, a rapidly developing country. And they employed a “continuous-time heterogeneous agent dynamic general equilibrium model,” which incorporated a task-based view of production.

The group’s model used continuous time, not time broken up into discrete intervals such as quarters or years, allowing them to use differential and integral calculus in their analysis. They used the perpetual youth model developed by Oliver Blanchard in 1985, which accounts for finite lifetimes and individual differences in the lives, income trends and deaths of residents.

They built their model to assume that individuals in the economy all have the same ability to earn income from both labor markets and capital markets during their lifetime. They modeled mortality among individuals as a Poisson process where the death rate is known but individual deaths can occur at random.

To be sure, AI is a complex, multi-faceted feature. After reviewing some of the attempts to specify what AI is exactly, the authors write, “These conflicting perspectives highlight the inconsistencies and unresolved debates within current research.” Moreover, “the effects of AI are not uniform and can vary significantly between developed and emerging markets.”

By focusing on China, they reduced the wide ranges and implications of AI. After a good amount of mathematics, they used Chinese data to calibrate their model, choosing 2010 as the baseline for their model’s dynamics, and empirically fitted five parameters and four indicators for the technological levels.

They assumed “Hicks-neutral” technological change, a concept first introduced in 1932 by John Hicks—”neutral” meaning any technological change that does not affect the balance of labor and capital in the products’ quantities of physical inputs and quantities of output of goods. For example, a Hicks-neutral change in a factory’s production process would be one that increases the efficiency of labor and of machinery (capital) by the same margin.

Using the specific parameters as determined by their calibration, they computed the model’s equilibrium values for interest rates, wages, output, and other variables—the final values after the model’s evolution had reached a steady state. Their model finds that Hicks-neutral technology increases overall economic output, improving both labor and capital productivity at the same time.

Confirming their first hypothesis, advancements in AI-driven automation exacerbated wealth inequality, especially between labor and capital incomes, with the former increasing slower than the latter.

The economic expansion from AI does drive up wages, reflecting a higher overall productivity, but also increases interest rates driven by an increased demand for capital by businesses looking to incorporate AI in their workflows and by companies building ever better AIs. (Big tech companies are expected to spend $300 billion on AI this year alone.)

Wages increase, but less rapidly than capital returns, the latter having a disproportionate gain in efficiency. But their results are mixed: “Overall, these findings reveal that automation-driven AI strongly boosts output but intensifies wealth inequality,” Liu and Liang write, “while Hicks-neutral and capital-augmenting technologies foster broad-based growth and mitigate wealth disparities. Labor-augmenting progress raises wages and output without affecting wealth distribution.”

Finally, they propose policy interventions the Chinese government can undertake to mitigate any potential exacerbation of wealth inequality due to advancements in AI, for example “through secondary distribution mechanisms” and policy choices that balance growth incentives with wealth distribution objectives by fostering progress in Hicks-neutral technologies.

More information:

Fang Liu et al, Analyzing wealth distribution effects of artificial intelligence: A dynamic stochastic general equilibrium approach, Heliyon (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2025.e41943

© 2025 Science X Network

Citation:

How will artificial intelligence affect wealth equality? (2025, March 11)

retrieved 11 March 2025

from https://phys.org/news/2025-03-artificial-intelligence-affect-wealth-equality.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.