It took two years for NASA’s OSIRIS-REx space probe to return from asteroid Bennu before dropping off a small capsule as it flew past Earth, which was then recovered in the desert of the U.S. state of Utah on September 24, 2023. Its contents: 122 grams of dust and rock from asteroid Bennu.

The probe had collected this sample from the surface of the 500-meter agglomerate of unconsolidated material in a touch-and-go maneuver that took just seconds. Since the capsule protected the sample from the effects of the atmosphere, it could be analyzed in its original state by a large team of scientists from more than 40 institutions around the world.

The partners in Germany were geoscientists Dr. Sheri Singerling, Dr. Beverley Tkalcec and Prof. Frank Brenker from Goethe University Frankfurt. They examined barely visible grains of Bennu using the transmission electron microscope of the Schwiete Cosmochemistry Laboratory, set up at Goethe University only a year ago. The work is published in Nature.

Its goal: to reconstruct the processes that took place on Bennu’s protoplanetary parent body more than four billion years ago and ultimately led to the formation of the minerals that exist today. The Frankfurt scientists succeeded in doing this by analyzing the mineral grains’ exact structure and determining their chemical composition at the same time. They also carried out trace element tomography of the samples at accelerators such as DESY (Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron) in Hamburg.

“Together with our international partner teams, we have been able to detect a large proportion of the minerals that are formed when salty, liquid water—known as brine—evaporates more and more and the minerals are precipitated in the order of their solubility,” explains Dr. Sheri Singerling, who manages the Schwiete Cosmo Lab. In technical terms, the rocks that form from such precipitation cascades are called evaporites. They have been found on Earth in dried-out salt lakes, for example.

“Other teams have found various precursors of biomolecules such as numerous amino acids in the Bennu samples,” reports Prof. Frank Brenker. “This means that Bennu’s parent body had some known building blocks for biomolecules, water and—at least for a certain time—energy to keep the water liquid.”

However, the break-up of Bennu’s parent body interrupted all processes very early on and the traces that have now been discovered were preserved for more than 4.5 billion years.

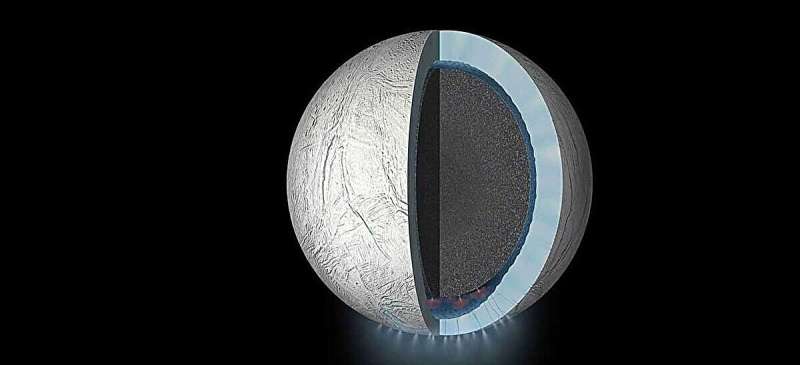

“Other celestial bodies such as Saturn’s moon Enceladus, or the dwarf planet Ceres have been able to evolve since then and are still very likely to have liquid oceans or at least remnants of them under their ice shells,” says Brenker.

“Since this means that they have a potential habitat, the search for simple life that could have evolved in such an environment is a focus of future missions and sample studies.”

More information:

Tim J. McCoy et al.: An evaporite sequence from ancient brine recorded in Bennu samples. Nature (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-08495-6, www.nature.com/articles/s41586-024-08495-6

Provided by

Goethe University Frankfurt am Main

Citation:

Dust from asteroid Bennu suggests solar system’s potential for life was widespread (2025, January 29)

retrieved 29 January 2025

from https://phys.org/news/2025-01-asteroid-bennu-solar-potential-life.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.