Observing the effects of special relativity doesn’t necessarily require objects moving at a significant fraction of the speed of light. In fact, length contraction in special relativity explains how electromagnets work. A magnetic field is just an electric field seen from a different frame of reference.

So, when an electron moves in the electric field of another electron, this special relativistic effect results in the moving electron interacting with a magnetic field, and hence with the electron’s spin angular momentum.

The interaction of spin in a magnet field was, after all, how spin was discovered in the 1920 Stern Gerlach experiment. Eight years later, the pair spin-orbit interaction (or spin-orbit coupling) was made explicit by Gregory Breit in 1928 and then found in Dirac’s special relativistic quantum mechanics. This confirmed an equation for energy splitting of atomic energy levels developed by Llewellyn Thomas in 1926, due to 1) the special relativistic magnetic field seen by the electron due to its movement (“orbit”) around the positively charged nucleus, and 2) the electron’s spin magnetic moment interacting with this magnetic field.

Now a spin-orbit coupling that had previously been neglected is found to possibly be strong enough to give rise to an unconventional type of superconductivity in certain materials. The study by Yasha Gindikin and Alex Kamenev of the University of Minnesota is published in Physical Review B.

The neglected coupling is from the Rashba effect, due to the combined effect of a spin–orbit interaction and asymmetry of the crystal’s potential, resulting in a force perpendicular to a two-dimensional plane. (The effect was first discovered in three dimensions in 1959.)

The Rashba spin-orbit coupling allows a way to control spin states using electrical rather than magnetic means. It has been crucial to the development of “spintronics,” electronics based on the spin of the electron, and was the basis for the proposal of the spin transistor.

The effect depends on the product of spin and angular momentum (hence the coupling), taking their directions into account, and in particular varies as the square of the product of the nucleus’s atomic number and fine structure constant.

It’s small at a low atomic number, due to the square of the fine structure constant (≈ 1/137) but becomes significant when the atomic number is large. It’s especially strong when the spin and the angular momentum (regular angular momentum, not spin angular momentum) point in the same direction, and zero when they are perpendicular.

The Rashba effect can arise in a crystal lacking inversion symmetry—inversion symmetry is invariance of an object after reflection around a point—as spin up and spin down electrons separate into different conduction bands—”lifting the spin degeneracy of conduction band electrons at finite momentum,” they write.

The study by Gindikin and Kamenev focused on the extensive Rashba spin-orbit interaction, produced by electric fields external to a crystalline lattice. Extensive Rashba spin-orbit effects are unavoidably proportional to the external electric field. Because of the dual conduction bands, the pair spin-orbit interaction comes from the electric forces (Coulomb forces) of one band on the other bands electrons.

An inversion asymmetry is no longer necessary. “This key insight—that the electric field… can arise from the Coulomb forces—opens up an entirely new research avenue,” the co-authors write. The Coulomb fields can reach magnitudes as high as 100 million volts per centimeter.

In particular, they propose that in certain materials, this pair spin-orbit interaction can be strong enough to give rise to an unconventional form of superconductivity. The spin-orbit coupling can cause electrons to pair up, much like Cooper pairs, and produce a superconducting state with odd parity.

The “Rashba spin-orbit coupling of conduction band electrons, a result of the band mixing with spin-orbit-split valence bands, manifests itself in electron-electron interaction effects.”

Their extensive calculations predict that the state would be easily disrupted by modest amounts of charged impurities and structural defects, giving rise to local fields and an extrinsic Rashba spin-orbit interaction, but the superconducting state would be detectable if the crystal samples were extremely pure and at temperatures of a few hundred millikelvin.

The team explored two consequences of the pair spin-orbit interaction. First, this coupling induces p-wave superconducting pairing, where Cooper pairs—pairs of electrons that move together through the superconductor with no resistance—have a specific angular momentum and the paired electrons have parallel spins, unlike conventional superconductors where the Cooper pairs have opposite spins.

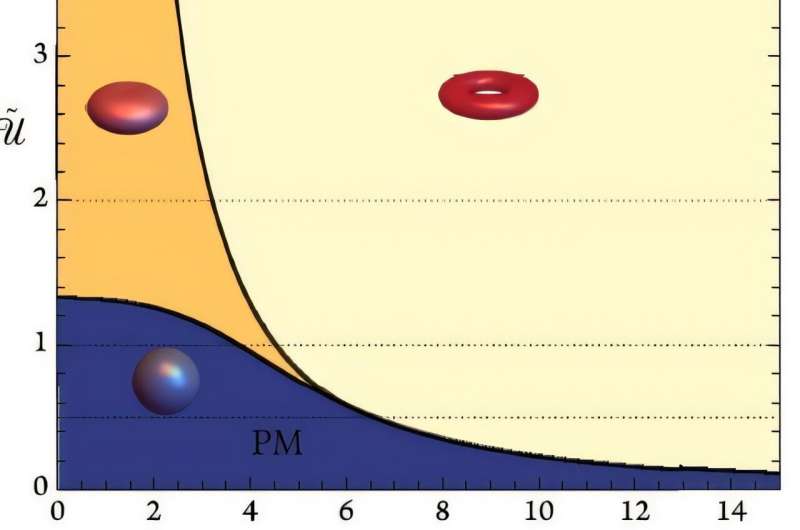

The second consequence of the pair spin-orbit interaction found by the authors is its role in facilitating Bloch ferromagnetism, an idea put forth by the physicist Felix Bloch in 1929, “suggesting,” as Phys.org covered in 2020, “that at very low densities, a paramagnetic Fermi ‘sea’ of electrons should spontaneously transition to a fully magnetized state.”

Their research, the authors write, “opens an exciting research avenue of searching for materials with a giant, tunable Rashba effect.”

More information:

Yasha Gindikin et al, Electron interactions in Rashba materials, Physical Review B (2025). DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevB.111.035104. On arXiv: 10.48550/arxiv.2310.20084

© 2025 Science X Network

Citation:

Relativistic spin-orbit coupling may lead to unconventional superconductivity type (2025, January 16)

retrieved 16 January 2025

from https://phys.org/news/2025-01-relativistic-orbit-coupling-unconventional-superconductivity.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.