Almost 300 binary mergers have been detected so far, indicated by their passing gravitational waves. These measurements from the world’s gravitational wave observatories put constraints on the masses and spins of the merging objects such as black holes and neutron stars, and in turn this information is being used to better understand the evolution of massive stars.

Thus far, these models predict a paucity of black hole binary pairs where each black hole has around 10 to 15 times the mass of the sun. This “dip or mass gap” in the mass range where black holes seldom form depends on assumptions made in the models; in particular, the ratio of the two masses in the binary.

Now a new study of the distribution of the masses of existing black holes in binaries finds no evidence for such a dip as gleaned from the gravitational waves that have been detected to date. The work is published in The Astrophysical Journal.

A star’s core is the extremely hot, dense region at its center, a volume where temperature and pressure allow the production of energy though thermonuclear fusion of hydrogen into helium. The “compactness” of the core is a measure of how dense the core is relative to its radius; it’s essentially the ratio of the core mass to core radius.

Theoretical models of stars suggest that the compactness of stellar cores does not increase monotonically with stellar mass, as might be suspected. Instead, there appears to be a dip in the core compactness for a certain core mass range which depends on the star’s metallicity (the fraction of its mass made of elements heavier than hydrogen and helium) and its mass transfer history—the transfer of mass from and to other stars.

Core compactness is also a proxy for a star’s explosiveness—a lower core compactness favors a supernova explosion. Stars near the mass of the compactness dip are expected to explode into supernovae, leaving behind a neutron star. But stars with masses on either side of the dip are predicted to avoid explosions altogether and collapse into black holes known as “failed supernovae,” or to form black holes after weaker explosions and partial fallback.

This disparity is predicted to cause a gap in the resulting distribution of black hole masses, in particular between 10 and 15 solar masses.

In terms of gravitational waves, the gap is expected as a dip in the “chirp mass” of the binary pair. The chirp mass of the pair is a certain mathematical combination of the two component black hole masses; it affects the frequency evolution of the detected wave as the distance between black holes gets smaller and smaller (the adjective “chirp” comes from an analogy with sound waves.)

Previous work suggested there is evidence in the gravitational wave data for a dip in the chirp mass between 10 and 12 solar masses, and also by population analysis of the binary black hole chirp mass distribution. The latter found support for the gap at within a 90% credible interval.

However, relating the predicted features of the individual masses to the chirp mass requires additional assumptions about the pairing between the two masses in a merging binary. One is that the individual masses are nearly equal. However, without this assumption, an inferred 10 to 12 solar mass chirp mass gap cannot be a reliable proxy for a 10 to 15 solar mass component mass gap. (The chirp mass is always smaller than the individual component masses because it is a weighted geometric mean.)

Using new data from the latest (the third) gravitational-wave catalog from 250 gravitational wave detections, lead author Christian Adamcewicz of Monash University in Australia and other Australian colleagues probed the distribution of black hole binary components to look for evidence of the chirp mass gap.

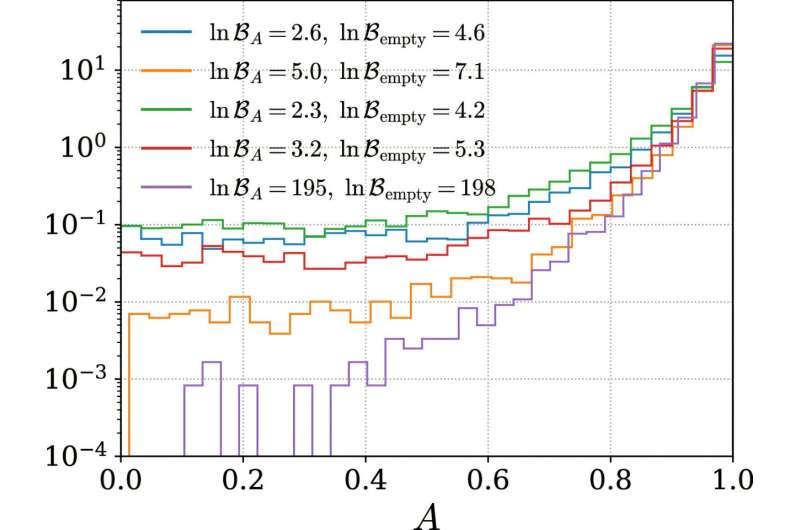

They began by constructing a population model for black hole binary component masses including a gap, using a proposal set out earlier.

“This model has the flexibility to capture the key features of the [binary black hole] mass distribution outside of the gap range,” they wrote, cross-checking it against curve fits to known mass distributions. They then added a flexible gap to their one-dimensional model using a notch filter with parameters that governed the upper and lower edges of the gap and its depth.

Using this model as a basis, they constructed a two-dimensional model for the two component black holes of the binary, but did not specify how the component black holes pair with one another. They used previously written software to model the spin distributions of the components.

Applying the gravitational wave data from the third catalog, Adamcewicz and co-authors found that it is “consistent with” the presence of a gap in binary component masses in the range of 10 to 15 solar masses (each), as was predicted, and also consistent with a dearth of component masses between 14 and 22 solar masses, as was also predicted.

“However, there is no significant statistical preference for any such feature,” they concluded. Their results showed “no preference for the case of a completely empty gap… over the case of no gap at all.”

That’s “perhaps not unsurprising,” they wrote, noting that a previous work found that an underabundance of binary black holes can sometimes occur due to statistically random noise.

Moreover, they found that the component mass dip, if it exists in nature, is unlikely to be “resolvable” by the end of the current Observing Run 4 (O4) which concludes on June 9, 2025, involving the LIGO, Virgo (Italy) and KAGRA (Japan) gravitational wave observatories.

A better understanding of stellar core compactness and the fate of core collapsing supernovae will await later gravitational wave detections or larger gravitational wave observatories such as the proposed space-based Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA).

More information:

Christian Adamcewicz et al, No Evidence for a Dip in the Binary Black Hole Mass Spectrum, The Astrophysical Journal (2024). DOI: 10.3847/1538-4357/ad7ea8

© 2024 Science X Network

Citation:

Latest gravitational wave observations conflict with expectations from stellar models (2024, December 20)

retrieved 22 December 2024

from https://phys.org/news/2024-12-latest-gravitational-conflict-stellar.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.