A new study by Rice University researchers Sho Shibata and Andre Izidoro presents a compelling new model for the formation of super-Earths and mini-Neptunes—planets that are 1 to 4 times the size of Earth and among the most common in our galaxy. Using advanced simulations, the researchers propose that these planets emerge from distinct rings of planetesimals, providing fresh insight into planetary evolution beyond our solar system. The findings were recently published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

For decades, scientists have debated how super-Earths and mini-Neptunes form. Traditional models have suggested that planetesimals—the tiny building blocks of planets—formed across wide regions of a young star’s disk. But Shibata and Izidoro suggest a different theory: These materials likely come together in narrow rings at specific locations in the disk, making planet formation more organized than previously believed.

“This paper is particularly significant as it models the formation of super-Earths and mini-Neptunes, which are believed to be the most common types of planets in the galaxy,” said Shibata, a postdoctoral fellow of Earth, environmental and planetary sciences. “One of our key findings is that the formation pathways of the solar system and exoplanetary systems may share fundamental similarities.”

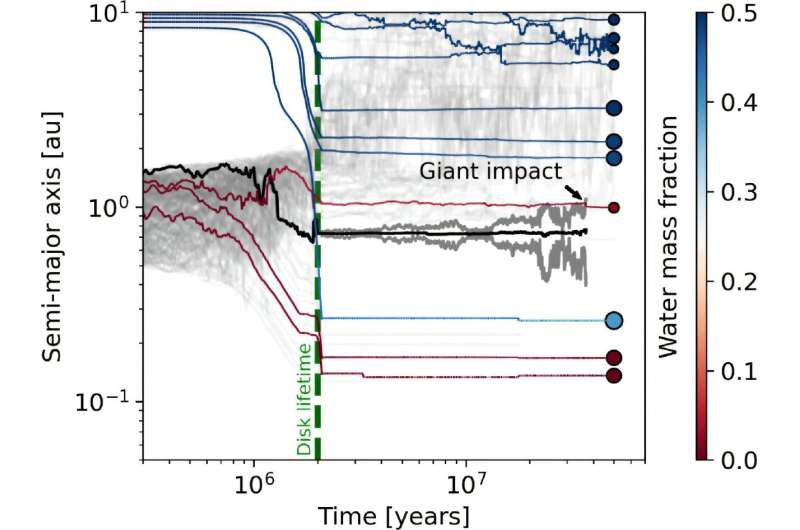

Using advanced N-body simulations—computer models that analyze how objects interact through gravity—the researchers studied planet formation within two distinct regions: one inside 1.5 astronomical units (AU) of the host star and another beyond 5 AU, near the water snowline. The simulations tracked the collisions, growth and migration of planetesimals over millions of years. The results revealed that super-Earths primarily form through planetesimal accretion in the inner disk, while mini-Neptunes develop beyond the snow line, mainly via pebble accretion.

“Our results suggest that super-Earths and mini-Neptunes do not form from a continuous distribution of solid material but rather from rings that concentrate most of the mass in solids,” said Izidoro, an assistant professor of Earth, environmental and planetary sciences. ” Related research at Rice has explored aspects of this idea, but this new paper brings these concepts together into a single, coherent picture.”

The researchers’ model successfully replicates key features of exoplanetary systems, including the “radius valley”—a noticeable scarcity of planets around 1.8 times the size of Earth. Instead, exoplanets tend to cluster into two size groups: roughly 1.4 and 2.4 times Earth’s size. Their model explains this gap by predicting that planets smaller than 1.8 times the Earth’s radius are mostly rocky super-Earths, while larger ones are water-rich mini-Neptunes, aligning closely with real-world observations.

The research also provides insight into size uniformity observed in multiplanet systems. Many exoplanetary systems show a “peas-in-a-pod” pattern, where planets within the same system are strikingly similar in size. The ring model naturally produces this uniformity by controlling how planets form and grow within their respective rings.

Shibata and Izidoro’s simulations also align with observed distributions of planetary orbits, reinforcing the idea that planets emerge from specific locations rather than being randomly scattered across the disk.

Beyond explaining these observations, the model also allows for predictive analysis of planetary formation and even hints at the potential for other Earth-like planets. Izidoro said although it would be rare, rocky planets in the habitable zone could form through late-stage giant impacts, similar to how Earth and its moon formed.

“We can push our model further and use it to make predictions about the types of planets expected at Earth-sun equivalent distances—regions currently beyond the reach of observations,” Izidoro said.

“Based on our predictions, up to about 1% of super-Earth and mini-Neptune systems could host Earth-like planets within the habitable zone of their stars. While this fraction is relatively low given how common super-Earths and mini-Neptunes are, it implies an occurrence rate of approximately one Earth-like planet per 300 sun-like stars.”

Looking ahead, these findings could have profound implications for future exoplanet research.

“These predictions will be tested with future telescopes, providing crucial insights into planetary formation and habitability,” Shibata said. “If future observations confirm our predictions, it could completely change our understanding of how planets form—not just in our galaxy but throughout the universe.”

More information:

Sho Shibata et al, Formation of Super-Earths and Mini-Neptunes from Rings of Planetesimals, The Astrophysical Journal Letters (2025). DOI: 10.3847/2041-8213/ada3d1

Provided by

Rice University

Citation:

Super-Earths and mini-Neptunes research suggests more Earth-like planets may exist (2025, March 11)

retrieved 11 March 2025

from https://phys.org/news/2025-03-super-earths-mini-neptunes-earth.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.