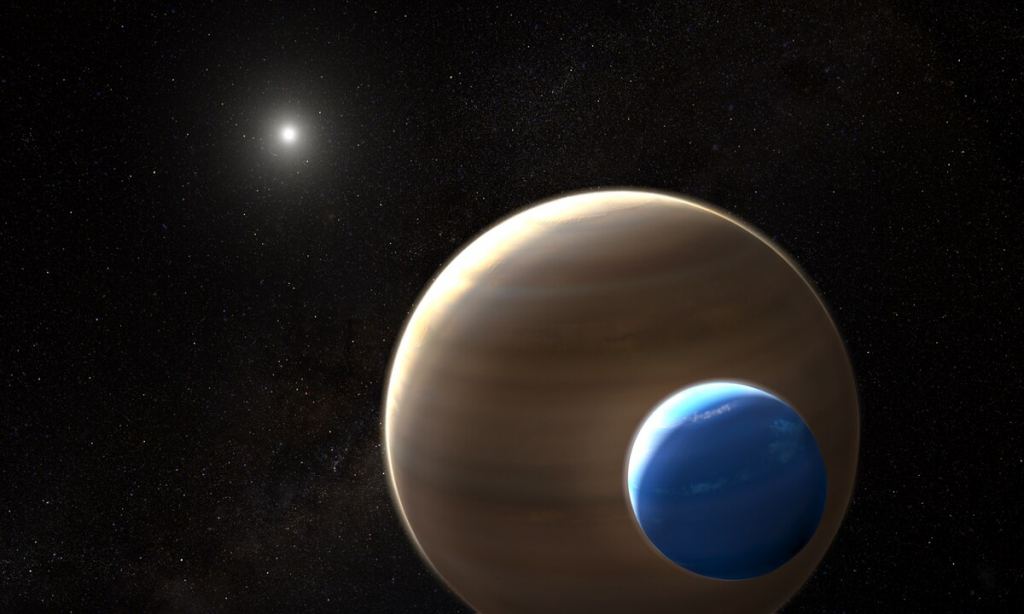

Exoplanets have captured the imagination of public and scientists alike and, as the search continues for more, researchers have turned their attention to the evolution of metallicity in the Milky Way. With this answer comes more of an idea about where planets are likely to form in our Galaxy. They have found that stars with high-mass planets have higher metallicity than those with lower amounts of metals. They also found that stars with planets tend to be younger than stars without planets. This suggests planetary formation follows the evolution of a galaxy with a ring of planet formation moving outward over time.

The search for exoplanets has largely been one of surveying nearby stars. That generally means we are exploring stars in our region of the Galaxy. As technology develops, our ability to detect them improves and to date, nearly 6,000 planets have been discovered around other stars. A number of different techniques have been used to find them such as the transit method – which detects the dimming of a star’s light due to the presence of the passage of a planet, or the radial velocity method which measures the wobble of a star due to the gravitational tug of a planet.

One key aspect of planetary development in the Galaxy is the presence of metals (elements heavier than hydrogen and helium.) known as metallicity. These elements are formed during the life cycle of a star, especially during supernova explosions. They are scattered through space and form part of the interstellar medium. Understanding the abundance and distribution of metals provides an insight into the age, history and formation rates of stars and planets.

A team of researchers led by Joana Teixeira from the University of Porto in Portugal have been exploring something known as the Galactic Birth Radii (rBirth) This term relates to the distance from galactic centre that stars and therefore planets are forming. Using photometric, spectroscopic and astrometric data, the team were able to estimate the ages of two groups of stars, those with planets and those without. This enabled them to rBirth for exoplanets based upon the original star positions (having calculated them from their age and levels of metals present within.)

The results of the analysis showed that stars hosting planets had a higher [Fe/H], are younger and were born closer to the centre of the galaxy than those without (Fe/H refers to the amount of iron relative to the amount of hydrogen in a star or galaxy, where the Sun is [Fe/H]=0.3.) The team went further to state that from one data set (from the Stellar Parameters of Stars with Exoplanets Catalog,) the results suggest that stars hosting high mass planets have a different iron to hydrogen radio and age distribution than stars with at least one low mass planet and those with only low mass planets.

The research reveals that high mass planets or in other words terrestrial planets tend to form around stars with higher [Fe/H] and younger stars compared to low mass. Similarly, those with a mixture of high and low mass planets also formed around higher [Fe/H], young stars.

It’s an interesting study worthy of further investigations. Understanding that Earth-like planets tend to form around star systems that formed around the inner regions of the Galaxy. Here the supply of metals is more abundant and, even though the stellar systems can migrate to outer regions of the Milky Way it gives a better focus on the hunt for planetary systems beyond our own.

Source : Where in the Milky Way Do Exoplanets Preferentially Form?