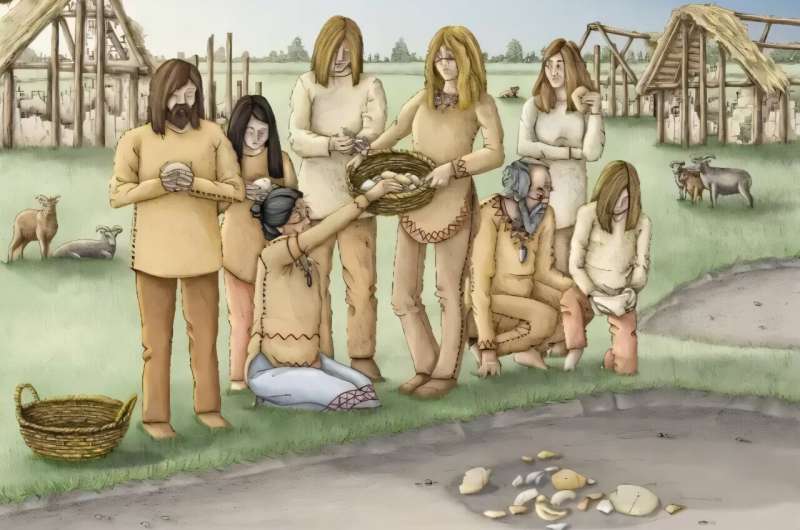

Archaeologists Dr. Jess Thompson and her colleagues have published a study dealing with the possible identification of human skulls used in ancestral veneration in the European Journal of Archaeology. The discovery at Masseria Candelaro (Puglia, Italy), an ancient village in Puglia, provides rare insight into how Neolithic people maintained connections with their ancestors.

During the Neolithic period in southern Italy (6000–3800 BC), funerary practices were diverse. They included primary and secondary burial, defleshing, and disarticulation.

The variety of burial practices found in Neolithic Italy, particularly the special treatment of skulls and bones, suggests these ancient communities saw human remains as spiritually significant, with the head holding special ritual importance.

Between 1985 and 1993, archaeologists Selene Cassano and Alessandra Manfredini were excavating the site of Masseria Candelaro.

“They were predominantly exploring the settlement remains, but in the process of their excavations, disarticulated human remains and burials turned up in a range of features across the site: the external ditches, disused pits and silos, and disused domestic spaces,” says lead researcher Dr. Thompson.

It was within Structure Q that the archaeologists discovered what is termed the “cranial cache.” Crania, belonging to a minimum of 15 individuals, possibly as many as 53 individuals, were recovered.

Using skull morphology and tooth wear patterns, the researchers determined that at least five individuals were male, six were probably male, and the rest were indeterminate. No children were deposited, with the youngest individual being between twelve and eighteen years old, while the oldest was likely older than 45.

The skulls showed signs of having been repeatedly handled, including extensive wear and dry breakage that could only occur after death.

There were two likely hypotheses for the deposition and repeated use of these skulls as Masseria Candelaro; the first was their use as war trophies, and the second was their use in ancestor veneration rituals.

Trophy skulls are usually acquired through violent means, which may result in physical trauma. However, within the cranial cache, no skulls showed signs of perimortem (around death) trauma, explains Dr. Thompson. “There’s (also) no evidence on the remains that were present in the deposit of any kind of perimortem trauma resulting from violent conflict, nor is there any indication of cannibalism, or any evidence that these crania had been embellished, ornamented or overmodeled.”

Additionally, strontium isotope analysis revealed the skulls had belonged to local individuals, making it unlikely, albeit not impossible, that these skulls were war trophies.

The evidence instead pointed strongly toward the second hypothesis: that these skulls were used in ancestor veneration rituals. Dating of the crania showed that the oldest skull was dated to ~5618–5482 BCE.

Over time, more skulls were added to the collection, likely one skull per decade up until the addition of the youngest skull, Cranium 1 ~5476–5336 BCE. The dates of the oldest and youngest skulls are particularly important as they show that their date ranges don’t overlap, providing definitive proof that these skulls were collected and curated over at least 200 years rather than being gathered all at once.

This indicates that skulls were added, handled, and deposited for up to eight generations. The criteria for who would become part of the cranial cache are uncertain. However, it is known that no children constituted the cache. In fact, children and infants are also only rarely found in any burials in southern Italy, perhaps owing to them not being deemed full persons yet or their lack of ability to become ancestors. Additionally, it is likely that individuals had to be male, as all identified and tentatively identified individuals were male.

Sadly, beyond these selection criteria, it is unknown what factors were used. It is possible that individuals were chosen based on kinship, societal role, or mode of death. What was not a deciding factor was age, as individuals from various age ranges were part of the cache, meaning older individuals were not chosen due to perceived seniority, knowledge, or life experiences.

After two centuries, around 5459 BC, the crania were deposited one last time in Structure Q and abandoned. Exactly why these crania were taken out of circulation or perhaps transformed into ex-ancestors is unclear; however, it is possible the type of ancestor veneration was abandoned in favor of another that did not require skulls.

Another is simply that the skulls had passed beyond living memory. Meaning that none of the living individuals at Masseria Candelaro knew who these skulls were. Without a link to the living, they could no longer serve as ancestors, and they were abandoned.

“Future analysis should seek to integrate these idiosyncratic burial deposits such as this cranial cache at Masseria Candelaro within their regional and wider context, in terms of the full suite of funerary practices which were being carried out at this time. This will enable us to better understand who received particular kinds of rites after death, at what scale these decisions were made (e.g. were variations specific to each village, or across wider landscapes of interconnected communities?),” says Dr. Thompson.

More information:

Jess E. Thompson et al, The Use-Life of Ancestors: Neolithic Cranial Retention, Caching and Disposal at Masseria Candelaro, Apulia, Italy, European Journal of Archaeology (2024). DOI: 10.1017/eaa.2024.43

© 2025 Science X Network

Citation:

Neolithic Italian skull cache suggests centuries of ancestor veneration rituals (2025, January 9)

retrieved 9 January 2025

from https://phys.org/news/2025-01-neolithic-italian-skull-cache-centuries.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.