Over the past two decades, large genetic studies have linked tens of thousands of DNA variants to thousands of human traits and diseases. Yet, correcting the effects of those variants to treat disease has been hampered in part by the lack of precise molecular tools to do so.

Researchers at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Massachusetts General Hospital, and Harvard University took a fresh approach by building a remarkably diverse collection of molecular compounds that can be mined for those that target disease-related genetic variants in new ways. Thanks to innovative chemistry methods, the library includes more than 3 million compounds designed to bring two proteins together and use one as a shield to stabilize the other and reverse its disease-related effects.

From their library, the team identified a compound that targets a protein altered in some patients with Crohn’s disease and showed that it can reverse the variant’s detrimental effects on the cell. The approach could potentially be used to recruit proteins with other functional effects or target disease risk factors in only certain cell types or tissues.

The new work appears in Cell Chemical Biology.

“Advancements in small-molecule chemistry have given us a real opportunity to come up with precise approaches to correct, modify, or activate genetic variants,” said Ramnik Xavier, a core institute member, director of the Immunology Program, and co-director of the Infectious Disease and Microbiome Program at the Broad. “In this study, we’ve built on our mechanistic understanding of this Crohn’s disease variant to generate a powerful chemical toolbox for correcting the variant while maintaining the gene’s function.”

Xavier is also a professor at Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital, and led the work along with co-senior author Stuart Schreiber, a founding core institute member emeritus of the Broad, and first author Zher Yin Tan, a graduate student in the Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology at Harvard studying under Schreiber and Xavier.

A new group of glues

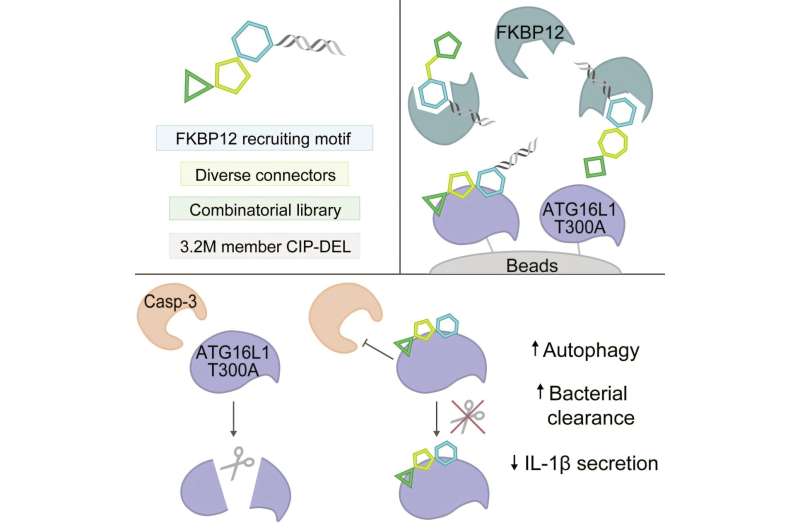

In their quest to find compounds that alter disease-related proteins in new ways, researchers have developed so-called chemical inducers of proximity, or CIPs, which include molecular glues and bifunctional compounds. These compounds bring together two proteins in the cell that might not normally find each other—a “target” protein (often the one altered in disease), and a “presenter” protein that has some effect on the target.

Until now, most CIP libraries have been aimed at triggering the dysfunctional protein to be degraded by the cell’s own waste processing machinery, thereby reducing its disease-causing effects.

In the new study, the researchers aimed to build a diverse library of potential CIPs that could do something other than degrade the target protein. For their presenter protein, they chose FKBP12, a well-studied protein that is abundant in human cells.

The team hypothesized that, when engaged by a CIP, FKBP12 might act as a shield to protect a target protein from enzymes that would otherwise break it down, effectively stabilizing it. For some disease-related proteins, this could be enough to restore their normal function as a way to treat disease.

The team aimed to cover as much “chemical space” as possible with their library by generating a large variety of molecular components that might recognize and bind a target protein. Each compound also includes a motif that binds FKBP12, so it can be recruited to the target.

In addition, they attached to each compound a unique DNA barcode—such “DNA-encoded libraries” allow researchers to efficiently pool millions to billions of compounds in a single experimental screen. The team also explored a variety of connecting elements to link the components of each compound together, using rigid linkers of different angles and lengths instead of the long, floppy chain linkers used in previous CIP libraries.

With different combinations of diverse linkers and target-binding elements, the team generated a CIP DNA-encoded library (CIP-DEL) of more than 3 million unique compounds that recruit FKBP12. To demonstrate their library’s potential for uncovering useful new CIPs, they took aim at a genetic variant, ATG16L1 T300A, which is associated with risk for Crohn’s disease.

One role of the ATG16L1 gene is to facilitate autophagy, a crucial process that removes harmful bacteria and waste from cells. A decade of work in the Xavier lab had shown that the ATG16L1 T300A variant of this gene impairs autophagy because the protein it encodes is more susceptible to cleavage by the enzyme caspase-3. So the team thought that shielding the protein from cleavage with a CIP could help restore autophagy and bring the cell back to a healthy state.

In an experimental screen, the team identified a compound that interacted with the ATG16L1 protein variant. Through further testing in human and mouse cells, they showed that it stabilized the protein, protected it from caspase-3 cleavage, and reversed the impairment of autophagy and other cellular processes without affecting caspase-3 activity, which plays other crucial roles in cells throughout the human body.

“There is so much potential in the new chemistry approaches of molecular glues, DNA-encoded libraries, and chemo proteomics,” said Xavier. “When combined with human genetics and deep mechanistic understanding, they give us innovative ways to pursue potential new therapeutic strategies.”

The researchers aim to next develop a version of the compound that works in animal models so they can further explore therapeutic opportunities. They also hope to see others customize the CIP-DEL library to target different disease variants and recruit presenter proteins with other functionalities, such as disrupting protein interactions or intracellular signaling pathways.

And by choosing presenter proteins that are only in certain cell types, a library could reveal CIPs that work with even more precision by altering cells in only disease-affected tissues rather than across the whole body.

“Our approach is a plug-and-play system,” said Tan. “Depending on the disease and molecular mechanisms you want to go after, you can design a unique library to find the types of compounds you’re looking for. We have much more chemical space to cover, and we’re hoping to contribute to the therapeutic toolbox to bring new ways of intervening across human disease.”

More information:

Zher Yin Tan et al, Development of an FKBP12-recruiting chemical-induced proximity DNA-encoded library and its application to discover an autophagy potentiator, Cell Chemical Biology (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2024.12.002

Provided by

Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard

Citation:

Scientists create vast library of compounds to target disease proteins (2025, January 6)

retrieved 6 January 2025

from https://phys.org/news/2025-01-scientists-vast-library-compounds-disease.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.